The British comedy series Steptoe and Son was first broadcast in 1962 and ran for twelve years. It was written by Ray Galton and Alan Simpson, who first met in a sanatorium in Surrey, England when they were recovering from tuberculosis. Together, they became one of the most prolific, famous and successful comedy-writing duos that this country has ever produced, as they collaborated on the hugely popular radio and television series Hancock’s Half Hour with the late Tony Hancock, which ran from 1954 until 1961 (including the series Hancock) and of which 170 episodes were recorded. Following the ending of their partnership with Tony Hancock in 1961, Galton and Simpson were given a ten-episode series by the BBC, entitled Galton and Simpson’s Comedy Playhouse. One notable episode in they series, The Offer, starring Harry H Corbett and Wilfred Brambell, was picked up by the BBC and became a series in its own right – Steptoe and Son.

Steptoe and Son tells the story of Albert and Harold Steptoe, father and son owners of a rag and bone business based in Shepherd’s Bush in west London. The dynamic between the two characters is that of Harold, who yearns to ascend above and beyond his life as a simple rag and bone man stuck in London living with his father despite being in his late thirties, with his father, who frustrates Harold in everything that he tries to do and whose occasional jolts of world-weary realism will invariably make the wheels come off every scheme that Harold comes up with to better himself. Steptoe and Son is proof of the incredible comedic potential that can come from the relationship between two people; throughout the whole series there were no other regular characters than Albert and Harold, though of course there were other characters which featured in most episodes, from girlfriends to milkmen to vicars to policemen. But the core dynamic was of two people, a generation apart, manacled together by both circumstance and necessity.

In the episode My Old Man’s a Tory, first broadcast on BBC Television in November 1965, we are met with an opening scene where Harold, on his rag and bone round, is returning home with his horse and cart. The cart is festooned with placards – ‘Vote Labour’ and ‘Let’s Go With Labour’ and Harold himself of wearing a large Labour rosette on the lapel of his overcoat. Meanwhile, Albert is at home, busy nailing placards supporting the Conservative Party to the front gate of their yard. As Harold and his horse and cart pull up towards the gate, Albert retreats hastily back indoors. His son, incensed at his father’s work, immediately begins to tear down the placards and throw them into the bin. Then, seeing ‘Vote Tory’ painted in huge white letters on the side of the house, takes a paintbrush and immediately paints over Albert’s work.

Meanwhile, Albert, hearing the sound of the horse arriving, sneaks upstairs. Harold, now angry at the sight of the numerous Tory posters, heads straight indoors to the front room to confront his father. But his dad has crept back downstairs and slipped out of the front door to remove the Labour posters which were pinned to the horse and cart. The two get into a heated debate about Albert’s Tory affiliations and how he wouldn’t have his false teeth were it not for Labour. Harold wonders why his father, with barely a penny to his name, would support a party like the Conservatives. Albert responds by saying that if Labour got control of the local council, the rates would go up within five minutes. They head back indoors, where Harold tells his father that the local Labour ward committee has been invited to hold their meeting later that evening at their house.

Albert objects, saying that he does not want the name of his business associated with a ‘a bunch of red scruffbags’. He also says that business should not associate themselves with any political party, as customers will be split right down the middle. He then undermines his point somewhat by saying the Labour junk is not as good as Tory junk. Harold reveals the reason for hosting the meeting – he holds political aspirations. He wants to make his mark in politics through the Labour party and the meeting at Oil Drum Lane is the first step on his way to greater things. Harold correctly identifies that class discrimination prevents people like him from ‘getting on’ and that he has been fighting it all his life. He asks the question “Why should not a rag and bone man attain the highest office in the land?”.

Albert offers his support to Harold in his coming election campaign – Harold, skeptical, wonders if his father is either pulling his leg or has made a complete pivot on his politics. But no. Instead, Albert sees his own opportunity to make a fortune in dealing with all the scrap that would be salvaged from the civic projects that the Labour council would commission. Harold, appalled at his father, retreats upstairs to get himself ready for the important meeting later that evening – in 1965, it would take more than a “flat cap, a red tie and a pair of hobnailed boots” to impress the Labour party machine.

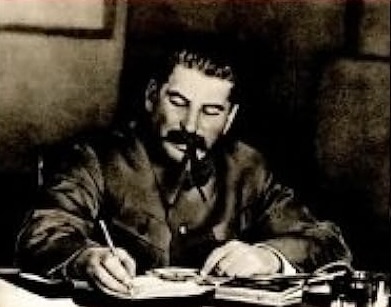

The scene is set for the meeting. The front room is decorated with Union Flags and, at the centre, is a portrait of Harold Wilson, pipe in mouth, wearing his signature raincoat. Harold then enters, wearing a raincoat of his own and with a smoking pipe in his mouth, but not being a regular pipe-smoker he coughs and splutters at the harshness of the pipe. Despite his best attempts, Harold cannot persuade his father to leave the house, or even leave the front room. The meeting will have to take place with his father in attendance. The attendees arrive – Harold greets them all as ‘comrade’ as they cross the threshold and make their way into the front room, followed by an agent from the Labour party, a well-spoken and clearly middle class man Mr Stonelake. Albert sits on a stool to the side of the room, looking on.

The formalities of the meeting take place. The minutes are read from the previous meeting – only three people were able to attend, which Harold puts down to a stomach bug but which Alberts claims was because Queens Park Rangers were at home that evening. Harold then read a resolution that was carried at the last meeting:

“The Ravensbury Ward Labour party of the Shepherd’s Bush constituency deplores the current situation existing in South Vietnam and calls upon the United States Government, the South and North Vietnamese Governments and the Vietcong to cease hostilities immediately.

To withdraw all foreign troops of South Vietnamese soil and to hold free elections under the supervision of the United Nations as agreed in the Geneva Convention of 1954.”

Copies of the resolution was sent to a number of dignitaries, including Harold Wilson (then Prime Minister) US President Lindon Johnson, Alexei Kosygin (Soviet Premier) and Ho Chi Minh (Vietnamese communist leader), among others. It was also confirmed that no replies had been received. The agent, Mr Stonelake, tells the meeting that it was rather hasty to send this motion to the world leaders and that official Labour party policy on Vietnam was clear (the Labour party conference in September 1965 supported the United States backing of the South Vietnamese in the conflict and this was later written into the 1966 General Election manifesto). Stonelake explains that resolutions such as this could only serve to embarrass the Government. Harold responded by saying that the motion captured the mood of the meeting, to which the agent replies “all three of them?”.

The meeting continues. A canvassing report is presented to the meeting, but the agent pours doubt on the figures given. Albert asks on what evening the canvassing took place, to which Harold replies “Tuesday’. Albert then points out that Riviera Police, a 1965 television programme, was broadcast on Tuesday evenings and people who were canvassed probably said that they would vote Labour to get rid of the canvassers so they could get back to their programme. Harold questioned this, but then Mr Stonelake agrees with Albert’s assertion. The agenda moves on to the nomination of candidate for the upcoming council elections – the secretary nominates Harold. Meanwhile, the agent nominates Dr Jeremy Stewart, to Harold’s confusion. Stonelake explains that the constituency party had decided not to endorse Harold’s candidature. Labour Central Office, responding to an influx of middle class people to the area, decided that the ‘cloth cap image’ would turn away potential voters.

Albert is incensed. He objects to the implication that his son isn’t good enough to stand and tears into Stonelake, telling him that he should get out. Amid the ensuing chaos and with the secretary announcing her resignation in protest, Harold calls the meeting to order and states that he would withdraw his name and offered Dr Stewart his full support. The meeting closes with the agent thanking Harold and telling him that the party won’t forget this. The attendees depart, leaving only Harold and his father remaining in the house. Albert, clearly upset at seeing his son so distressed, asks him if he feels disillusioned by the events of the evening. Harold claims that he is not, which Albert is not convinced by, but this begins a heated political argument between the two, as the episode draws to a close in the manner in which it began.

While a work of fiction, the treatment of Harold by the party machine will resonate with many who have had even the briefest involvement with Labour at any level. Its greatest engagement with the working class was arguably in the 1951 General Election and has been in a steady and inexorable decline ever since – even in 1965 it was in full pivot towards appealing to a more middle-class voting base. Labour has for decades sought to reduce the active electorate to as smallest possible number: It has believed for all this time that their best opportunity for electoral success comes when the battlefield is as small as possible. Some Labour dignitaries, like Peter Mandelson, were convinced that winning over the middle class (or at least the professional and managerial layer of the middle class, which is arguably still working class because they generally only have their labour power to sell) was key to any Labour victory because the working class had “nowhere else to go” but the Labour party.

The fact that what many believe is a recent phenomenon, which is Labour’s apparent abandonment of the working class in favour of more middle class politics, was actually identified by the contemporary culture of 1960s Britain shows clearly that this is a paradigm which has existed for decades, not since the elevation of Tony Blair or Sir Keir Starmer to Labour leader. Labour has never been a party either by or for the working class and it is wholly disingenuous of the party or indeed anyone else to claim otherwise.

Labour was founded by middle class groups like the Fabians, in association with what Lenin called the Labour Aristocracy: The section of the working class that not only benefitted most from imperialism, but had a vested interest in the continuation of imperialism, with all its pernicious effects on the peoples of lands thousands of miles away. Labour was founded not to deliver socialism to Britain, but the complete opposite – it is and has always been a deeply anti-communist party whose chief aim is to act as a roadblock to socialism, to support anti-communism wherever in the world it takes place, from the Soviet Union to Vietnam to Malaya. My Old Man’s a Tory is a work of fiction from almost sixty years ago which is as accurate of the realities within the Labour party today as it was when it was written.

‘My Old Man’s a Tory’ is available to view here on ITVX

Leave a comment