The recent news that Medway Council in Kent is considering introducing new rules on the licensing for homes in multiple occupancy (also known as HMOs) in an attempt to curb antisocial behaviour and poor housing standards is just one in a plethora of examples of the rise of the HMO and how these dwellings serve as an accurate indicator of the decline not only in the standards and availability of affordable housing, but of society generally.

The term HMO has only become common parlance in the last few years, but the phenomenon of homes being converted to multiple occupancy is not new.

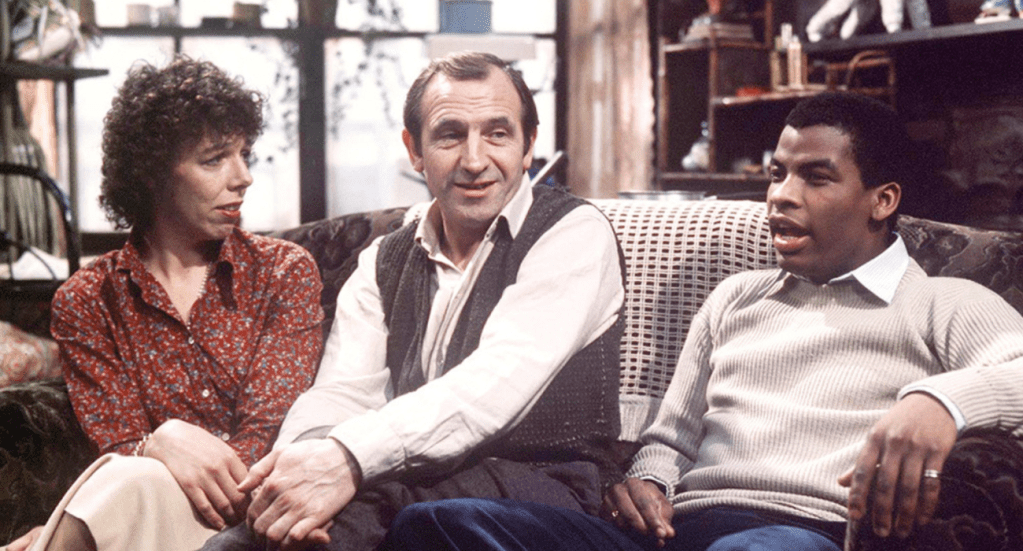

The 1970s situation comedy series Rising Damp was set in a large home divided into small bedsits, owned and run by Leonard Rossiter’s character Rigsby, the prejudiced skinflint whose affections for Frances De La Tour’s Ruth Jones character was unwavering. The series took its name from the real world problem which affects older brick-constructed buildings, which was ground water rising through brickwork via capillary action, known as rising damp. The literary link between damp and homes of multiple occupancy isn’t an accident: Other forms of damp, such as condensation damp, which is damp created from within a dwelling and penetrating damp, which is essentially water ingress from the outside, can also occur in buildings, particularly buildings which are heavily occupied, have untreated walls and poor ventilation.

Homes in multiple occupancy have served various practical purposes for those who rent them over the decades: They have been digs for people from all sorts of walks of life, from students to young professionals to travelling tradesmen. However, the common thread which runs through all these would-be tenants is that their stays in these homes were always anticipated to be relatively brief – the sort of tenancy that would be expected to last for months at most, rather than years. But with the rise of the modern HMO, houses are being converted to multiple occupancy with a view to providing landlords with a long-term investment opportunity with the potential to bring much higher returns than could be realised if the house was rented out as is. The internet is replete with websites enticing and actively encouraging landlords to not only rent out houses, but to convert them into more risky but more lucrative HMOs.

The conversion from a house to a HMO usually involves the house being extended, commonly into the rear garden, which allows the landlord to either add extra rooms or to make the existing rooms bigger, or both. The house itself needs to be converted to HMO standards, which includes the provision of fire extinguishers, self-closing fire doors and fire action notices, which must be displayed throughout the building. The landlord must, at least if they want to be legal, apply for a HMO licence from the local council for the property, which can cost upwards of £500.

Whilst on their face these works appear potentially expensive and troublesome, the returns are extremely lucrative: The average rent for a room in London is £982 per month including bills, which can give a landlord with an extended property the opportunity to rake in upwards of £4,500 in rents per month from a single house. Landlords are also looking to convert buildings which have in the past been guest houses or care homes, primarily because the cost of conversions is lower (mainly because they already comply to a degree with current HMO standards), the cost of these larger buildings is, pro-rata, cheaper per room than a three or four bedroom house and the number of occupants (and therefore returns) is even higher than from a converted ‘regular’ house.

Meanwhile for renters, the financial case for renting a room in a HMO is extremely compelling: According to website Property118, the average rent for a single bedroom flat in London without bills is £1,651 per month, which would require the tenant to earn £30,000 per year gross just to live alone and keep a roof over their head and pay for their bills, let alone be able to afford luxuries like food and clothes.

The truth is that property prices, both in terms of outright purchases and rents, is being artificially inflated by a system which is deliberately constricting the supply of homes. It does this through legislation like those associated with protecting the ‘green belt’ (legislation which, though well-intended, has become a tool for restricting the amount of available land on which to build new homes), high land prices, restrictive planning laws and, crucially, existing home owners themselves, who have a vested interest in preventing local house building projects in order to protect the value of their own home.

It should also be considered that the number of single people seeking a home is also on the rise. As I wrote in my article ‘The Loneliness Phenomenon’ last year, the percentage of homes occupied by a single person was 27% as at 2012 and has inevitably risen above this figure in the period since. For people looking to move out of their parents’ home and strike out on their own, it hasn’t been this difficult to find a decent place to live in generations. It is inevitable that under capitalism, with society becoming increasingly atomised, wages under constant downward pressure and the cost of living continuing its inexorable rise, the subdivision of homes into HMOs would be the next logical step for potential tenants needing an affordable place to live and parasitic landlords looking to wring every penny from their prized assets.

For parasitic landlords, converting a home into a HMO to fleece people with nowhere else to live is not a plan without drawbacks. HMOs, with their crowded conditions, can give rise to antisocial behaviour, including loud music, drug abuse, improper waste disposal, inconsiderate parking and uncontrolled and untrained pets. Crowded conditions can lead to mental health issues, as well as physical illnesses through disease transmission, sleep deprivation or caused by the damp and mould which can be present in overcrowded and poorly maintained homes in multiple occupancy.

Some HMO tenants will end up there by dint of the fact that they claim Universal Benefit and that the Local Housing Allowance (LHA) for claimants under the age of 35 is often set at a lower rate. In many areas, this only covers the cost of shared accommodation, such as a room in an HMO, which means that tenants are effectively coerced into living in cramped dwellings where anti-social behaviour and poor housing standards exist.

The rise of the HMO isn’t by any means an accident: It’s the result of the inexorable decline and fall of the capitalist system – a system which already has enough places to live to comfortably home every person in this country, yet forces the poor and the vulnerable into overcrowded and run down slums owned by a parasitic landlord class whose first and last consideration is the extraction of profit. The return of social housing as a societal good in and of itself cannot come from capitalism, regardless of what the likes of Jeremy Corbyn, Zarah Sultana or Zach Polanski would have you believe.

The return of decent and affordable housing can only come from socialism, where the working class overthrow our oppressors and own and run the system for ourselves, building and having as a right the kind of houses that we would like to live in and raise our families, without being shackled in debt or forced into mouldy, cramped and overcrowded homes in multiple occupancy.

The Middle Aged Revolutionary and Comrade Terry sat down to discuss this article and the rise of the HMO. You can watch this on YouTube here.

Leave a comment