I have worked in transport for over thirty five years. For most of that time I have been a strong advocate for all modes of public transportation. Despite the often shocking price, the occasional catastrophic failures and the intermittent lack of choice of who gets to sit next you, I would often urge people looking to make a trip to at least look into the possibility of leaving the car at home and letting the train (or the bus, or both) take the strain. Travelling by car is often fraught with traffic congestion, depressing stops for the loo and something to eat, accidents, road rage, potholes and expensive petrol. Why not kick back with a good book or a podcast and just get there when you get there?

Still, my recent personal experiences of public transport journeys from hell have tested my faith to its limit and will lead me to be much more cautious when I consider advocating for public transport in the future.

My first bitter experience occurred at the beginning of September. I had my journeys to and from Wigan on the Friday and Sunday of that weekend disrupted by a points failure going there and serious overhead power line damage coming back. The Sunday return trip was particularly egregious – my train to London was cancelled, with the following one being formed of only nine coaches and was packed to the rafters by virtue of the preceding train being cancelled, so I was unable to board, let alone find a seat. I then took the following train, which was destined for Birmingham, where I boarded a half-empty eleven carriage train to Crewe. Changing at Crewe, my London Northwestern Railway train took almost four hours to get to London, was seriously overcrowded and held up by a missing driver, line congestion and the aforementioned overhead power line damage.

The second example of the consummate failure of public transport in this country was at the end of September, when I was away in Devon. It was a dreary Monday weather-wise, so we decided to hit the nearest Wetherspoon’s, which was in Honiton, for the afternoon (my article in praise of JD Wetherspoon is way overdue, but I’ll get onto it soon). Wishing to leave the car at home, we opted to catch the bus to Axminster and then the train to Honiton, which went quite smoothly going there (despite the bus being under diversion owing to flooding) but coming back our train from Exeter St Davids was late and the bus which we were supposed to catch from Axminster at 5.15pm didn’t turn up. The next bus (and last bus, scheduled at 6.42pm) would not arrive for over an hour.

With the taxi rank only occupied by a solitary pre-booked cab, we ended up with another couple in a taxi that my wife had called, splitting a £25 cab fare (the bus would have been £4 for the pair of us, had the damned thing turned up) to get us home before sundown. To date, I have no idea whatsoever what happened to the 885 bus from Axminster to Seaton that afternoon.

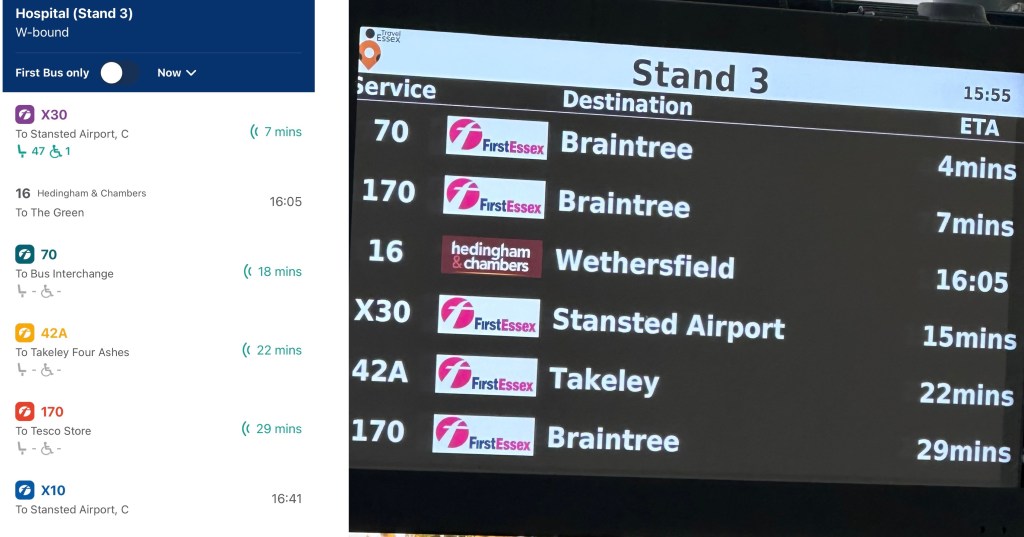

The third and final example of the utter crapness of British public transport was earlier in October. My wife and I travelled by bus to the hospital, where her 2.30pm appointment was delayed by over an hour for reasons that I have yet to fathom. It seemed that nobody at the hospital thought to contact anyone to warn them that appointments had been delayed, preferring instead to surprise them with this news when they arrived. Whilst sat in the waiting area, we looked at the times of the buses and deduced that we would in all likelihood be taking a very late bus home, which would not be getting us back until well into the evening. I suggested that I leave straight away, get the bus back home and return to the hospital in my car to collect my wife when her appointment was finished.

Having left the hospital, I waited for an hour and fifteen minutes for a bus back to where I live – one bus was terminated short and another refused entry to passengers, despite there being seats available on the upper deck. I checked both the First Bus app and the screen at the bus stop and found that both were giving wildly conflicting information. From leaving the hospital to getting home (a bus journey that should take 40 minutes) took over two hours and no sooner was I home than I was picking up my keys to drive my car back to Broomfield Hospital. I sent First Essex’s Twitter account my complaint and got only a mealy-mouthed apology and nothing else.

So Why Is Public Transport So Crap?

In the case of Britain’s railways, particularly in the case of the West Coast Main Line operated by Avanti, travellers have been victims of poor service, overcrowding, late-notice cancellations and failures of infrastructure for years. Reliability worsens at the weekends, especially Sundays, because the staffing model which Avanti West Coast and other train operating companies employ requires train drivers to work overtime to provide a service. In the working week, that means drivers working their rest days, while on Sundays, which are not part of the working week because of an agreement with railway workers which dates back decades, all work is done on overtime.

Part of the reason why train drivers are reluctant to work overtime is because they are already on competitive salaries and overtime is usually taxed at 40%, which means that after other deductions including pension and National Insurance, they will only see a little over half of the total cash value of their extra work. On top of this, drivers working their rest days in the week will be less inclined to work their day off on the Sunday, especially if they have children of school age.

The private operating model of Britain’s railways sees no worth in paying a train driver for anything other than driving trains – rather than having enough drivers available to cover every duty but consequentially having more cover available than required from time to time (which creates spare staff), operators employ less staff than they need and hope that there will be enough interest in overtime to fill the gaps. However, anyone who has suffered Britain’s railways, particularly at the weekends, will know that those gaps aren’t being filled and journeys are fraught with reliability issues. The private operating model has proven itself many times over to have been a consummate failure and only the full nationalisation of Britain’s railways, without compensation, will even begin to answer the myriad problems which beset our rail network.

On the buses, which were deregulated outside of London in 1985, how good, bad or indifferent they are largely depends on where you live. If you live in a major conurbation like London, Manchester or Liverpool for instance, you’ll be using a bus services managed by an authority, which sets standards for the operators (such as when the first and last buses run) and can enforce those standards accordingly. Outside these conurbations, things become a deregulated free-for-all – bus operators run services at times and with frequencies that suit them not the needs of passengers. Councils may put pressure on operators and are allowed to subsidise certain trips on certain routes, but beyond this councils know that they’re at best appealing to the better nature of private companies and private companies don’t have a better nature.

Currently, bus companies are being subsidised by the state to reduce fares to £2 per journey. Whilst a laudable scheme, which has been extended several times, the fact remains that the state is papering over the cracks in terms of the price of unregulated bus fares and has no answers to the poor standard of service. Patronage of bus services has been in decline since the 1960s and this decline was exacerbated exponentially by the Government’s cack-handed response to Covid.

In rural areas like Devon, some bus services end in the mid to late afternoon, meaning that people without a car of their own need to plan journeys to local towns around the paltry number of available services – in the case of travelling from Seaton to Honiton and back I outlined above, an eleven-mile journey, there are only three direct buses a day in each direction. Whereas bus services in major conurbations can be quite lucrative for operators and market forces drive them to provide services according to need, in less densely-populated areas, because of the low passenger numbers those market forces do not exist and services will be infrequent and not extend into the evenings in order to save on staffing and maintenance costs.

Deregulation of Britain’s bus services has been a disaster: Outside of major cities like London, Manchester and Liverpool, where buses are already regulated, a national bus regulatory authority, buttressed by the establishment of a publicly-owned and democratically run national omnibus company, could provide free travel to school children, those on low incomes and disabled people, as well as set rigorous minimum standards for routes, from the times of the first and last buses to the frequency and capacity of services. Privateers would be swept away in place of a national and fully integrated transport network, which would connect with major rail and other public transport services to provide more seamless journeys. Of course, the first step towards any of these solutions is the implementation of true worker-led socialism.

Leave a comment