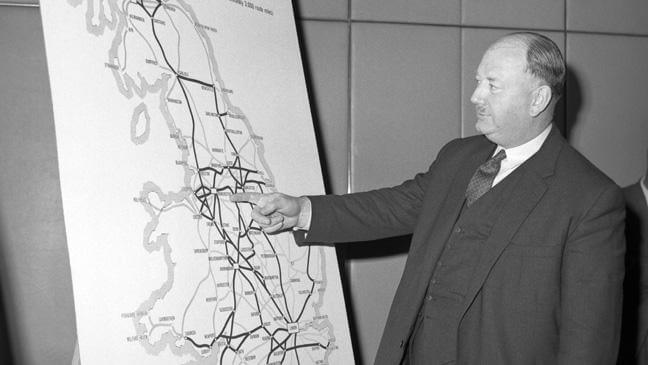

On 27th March 1963, British Railways published a report entitled “The Reshaping of Britain’s Railways”. The report, followed two years later by “The Development of the Major Trunk Routes”, detailed in full the lines and stations which, in the view of Dr Richard Beeching, the man who wrote both reports, should be closed permanently in order to restore British Railways to profitability. With these reports, and the subsequent recommended closures of some 30% of the rail network and over 50% of the nation’s stations, Beeching became a pariah, the man who destroyed Britain’s once magnificent railway network.

His reports and the implementation of their recommendations left towns and villages bereft of their railways, their stations closed, the links to conurbations, work locations and holiday destinations all permanently severed. To some, Beeching could only have conceived a plan to wreak such utter devastation out of sheer bloody-mindedness – British Railways had appointed a man who clearly must have hated railways with every fibre of his being, who wanted nothing more than to see the network he presided over be completely destroyed. Another point of view is that, with the appointment of Ernest Marples as Minister of Transport in the conservative Government in 1959, the fate of Britain’s Railways was sealed. Marples was instrumental in the commissioning and building of Britain’s first motorway, the M1, and was also the managing director of Marples Ridgeway, a road construction business, which suggests a clear conflict of interest.

The truth of course is a little more nuanced than that. Britain’s railways had been in very poor shape since the First World War and were not built in a planned manner in the first place. To build a railway line in the 19th century, one only had to form a company, borrow some money, get an act of Parliament to give you permission to build it and away you went. Some lines lost money from the minute they were opened until the moment that they closed – most of the lines built on the Isle of Wight are good examples of this. The advancement of technology, in particular in terms of road transportation, meant that cars were becoming more accessible to the ordinary working class man and woman. Hauling goods by road became much easier and, critically, much cheaper as larger containers could be hauled by road. Railway lines had already been closing in the inter-war period for reasons including poor passenger numbers and duplication or replacement of stations and services. Amongst the wider public of the time, the railways had become something of an anachronism.

In the post Second World War period, Britain’s railways were nationalised by the Labour Government in 1948, principally because they were bankrupt and in a state of utter disrepair following five years of war. They were no longer viable as privately-owned going concerns and, then as now, the Government stepped in to fill the breach where free-market capitalism had failed. The newly nationalised British Railways had a number of serious challenges to overcome, the chief of which was how it was to replace its steam locomotive fleet, which required an enormous amount of staff to operate and service. For the first twelve years of British Railway’s existence, they were compelled to continue to build steam trains, firstly according to designs inherited from the former private rail companies, then according to British Railways’ own designs. By way of comparison, fully electrified railways were being built in Switzerland as early as the 1920s.

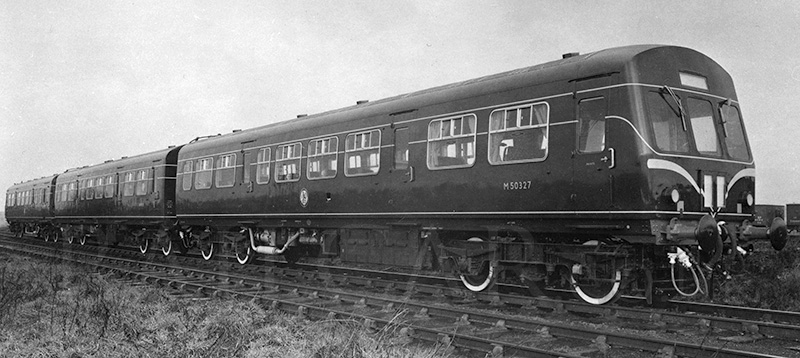

The British Transport Commission, which was established by the Clement Attlee Labour Government in 1948 as part of their nationalisation programme, introduced a ‘modernisation plan’ in 1955 which included what became known as ‘dieselisation’ – the replacement of steam engines with diesel locomotives and multiple units as a stop-gap until electrification could be brought online later on. This was despite senior British Railways officials including their de-facto Chief Engineer, Robin Riddles, being against dieselisation as the oil required would be prohibitively expensive and the coal required to run their existing steam fleet was very cheap and locally sourced. However, one key factor which at least partially explains the Government’s decision was the enormous amount of workers it required to operate and service steam locomotives – two men would be required to operate every loco (a driver and a fireman) and steam locos required daily cleaning, watering and fuelling as well as periodic servicing which included a full strip-down and rebuild, normally taking two weeks per loco.

Diesel, at least as far as the Commission was concerned, was cleaner and simpler – the fireman role could be abolished, leaving only a driver in the cab of each train, while refuelling could be done once a day and the servicing requirements were far less burdensome than for steam locomotives. Diesel multiple units did not have a locomotive on the front, so the process of swapping the loco from one end of the train to the other at terminal stations was abolished. Coupled (no pun intended) to the introduction of diesel trains was a project to electrify key sections of the network. This electrification would allow for the introduction of electric multiple units – electric trains which had advantages over even the brand new diesel trains, including no necessity to refuel, quicker acceleration and braking (owing to electric trains being far lighter than their diesel counterparts) and being much cleaner than diesel trains. It would also mean that electric locomotives could be introduced for long-haul passenger trains and freight, with similar benefits to the introduction of electric trains.

Yet with the addition of diesel and electric traction in the second half of the 1950s, as well as work towards the standardisation of coaches and major repairs and renovations taken on lines, passenger numbers on the railways did not rise as expected. According to Beeching’s report, one third of the British Railways network carried just 1% of the total passenger traffic. With the network haemorrhaging money and the modernisation programme not only costing more than was budgeted, but at the same time failing to inject new life into Britain’s railways, the British Transport Commission found itself unable to pay its debts, which were huge. The principle of closing down branch lines was already set in 1949, just a year after the BTC was founded, as a special department of the Commission dedicated to the managed decline of those lines was set up.

The Conservative Government of Harold Macmillan decided to take action. It appointed Richard Beeching, a businessman rather than a railwaymen, as the head of British Railways, then abolished the British Transport Commission and appointed the new British Railways Board in 1963. Beeching’s brief on his appointment was simple – cut the losses that British Railways was suffering. To this end, Beeching set about examining the railway network, counting its passenger numbers and looking at the costs of the running of British Railways. His report, “The Reshaping of Britain’s Railways”, proposed the closure of 5,000 miles of track and over 2,300 stations which were not only unprofitable, but loss-making. And, despite some notable resistance movements to save some of the lines proposed for closure, the vast majority of the miles of track and stations were closed down for good.

As far as passenger traffic was concerned, his theory was a simple one: Close down loss-making branch lines which connect into larger main lines and trunk routes, convert existing goods and coal yards attached to stations on these main lines into car parks and passengers could then drive their car from their town or village to the main line station, park there and catch their train. Alternatively, those without a car could use one of the hundreds of new bus services which the report recommended be introduced to travel to the main line station. The reality however was somewhat different. Instead of driving to the main line station to catch a train to where they wanted to go, people just got in their cars and drove straight to where they wanted to go. The bus routes introduced by Beaching were often poorly used and most of them were eventually withdrawn.

Another fatal error in the implementation of the Beeching report was the manner in which lines were closed. Any line identified for closure would see notices of closure posted at the affected stations, services would then be withdrawn and, crucially, the work would immediately begin on heaving up miles of rails, tons of sleepers and boarding up stations. There are very few examples of lines being simply mothballed, whereby the track and stations could remain intact, with a little light maintenance as required, just in case circumstances changed and the line could be reopened. The decision to close and then destroy lines completely has meant that towns and villages which once had a railway line connecting them to the mainline to major cities would never see them again.

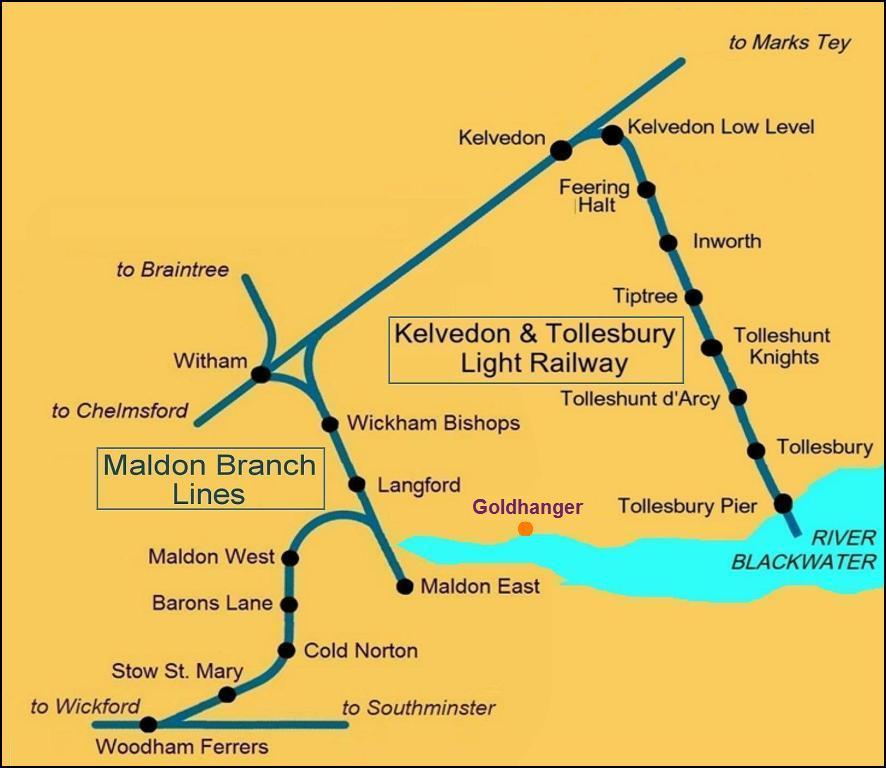

One good example is Maldon, a town in Essex famous for its sea salt. It once had two lines running into it connecting Maldon to two main lines – one between London and Southend-on-Sea and the other between London and Norwich. The branch from Witham to Maldon was closed to passengers in 1964 and to freight in 1966 as part of the recommendations of the Beeching report, while the line from Wickford to Maldon was closed in 1939. Maldon District, which includes the town, has seen its population increase by over 7% since 2011, according to the 2021 census, yet commuters living there have to drive or catch a bus from Maldon to Witham to get their train. Any notion that the old line to Maldon could be reintroduced are permanently dashed by the fact that a factory belonging to Bairds Malt, just to the east of Witham station, expanded after the closure of the line to completely subsume the land the line once occupied. No new line could now be built in the footprint of the old one.

The tearing up of closed railway lines was extremely short-sighted and has led to housing developments to roads to country parks taking their place permanently. When one compares the relatively cheaper cost of building new railway lines in the 1960s to the astronomical cost of building them now (see High Speed II), it makes the decision to remove railway lines even more baffling.

However, one key area where it can be argued that Beeching got it correct was in the field of freight. When it was nationalised in 1948, goods were transported by rail using wagons – complete vehicles with doors through which good could be loaded. Because of their size and the amount of freight which was generally carried per train, smaller goods and coal yards would be dotted along any given railway line. What Beeching proposed was the introduction of freight terminals – huge facilities where containers could be delivered and collected by lorries and/or container ships to be taken on to their final destination. The small goods and coal yards would be closed and, in many cases, converted into car parks.

One key advantage of transporting freight in containers is that trains no longer required to use wagons. Instead, locomotives haul flatbeds, huge platforms on wheels, onto which containers could be placed. These same containers could be loaded onto and off ships and lorries, rather than goods being handled manually, saving time and reducing the need for manpower. With the development of powerful diesel locomotives at the time, including the Deltics, freight trains could be longer, carry more goods and travel longer distances in less time. It is difficult to argue against Beeching’s recommendations on freight, as to this day we are still deploying the methods that he proposed.

In summary, Beeching’s reports and their recommendations were capitalist in nature and in their implementation. The fact that the Government of the time was a Conservative one has, frankly, no bearing on the report or its outcomes – the Labour Government of 1966-70 closed the majority of the lines and stations which were earmarked for closure and history has shown that they are absolutely no friend of the railways. Beeching’s report helped to transform the transportation of goods and helped birth a freight network which remains to this day. But Beeching’s deeply flawed approach to the rationalisation of Britain’s passenger railways caused permanent and irreparable damage to our rail network. Thousands of miles of railway lines have been lost forever under tarmac or housing, with stations repurposed as offices, private housing or businesses.

The Beeching cuts are a good example of the drawbacks of public ownership under the capitalist system. British Railways was publicly-owned, yet found itself under capitalist pressures to cut costs and turn a profit, pressures which resulted by 1975 in 12,000 miles of track being closed.

It didn’t even result in the return to profit that was intended.

It could be argued that, under a planned economy inheriting our railways in a similar state to those of Britain at the end of World War II, far greater sections of the network would have been electrified than under the modernisation period of the 1950s. To this day, only one third of the total rail network is electrified. A planned economy would be able to develop low-cost, low maintenance trains capable of operating increased services on branch lines, maintaining links to main lines and major conurbations. A planned economy would also not have persevered with steam engines well into the 1960s as British Rail did, instead replacing them with electric and diesel locos far sooner, with those trained in the maintenance of steam engines retrained to work in one of the many alternative roles available in the railways.

The Beeching report was a 1960s report written for a 1960s world. When we assess its impacts, this fact above all must be considered.

Leave a comment